In praise of sound wizards – Vangelis, Yves Chamberland (Davout), Patrice Quef (Miraval)

Vangelis passed away. Last year, Patrice Quef, the sound engineer of Miraval, died. Yves Chamberland, who founded the studio Davout and who once owned the Château d’Hérouville, is still alive and nobody knows it.

Vangelis died on May 17 in a hospital in Paris. Fleeing from the Greek junta, he first arrived in the city in 1968 after being denied entry into the United Kingdom. There, he recorded with his band Aphrodite’s Child several legendary albums, among which 666. That beast of a double concept album, drawing on the Apocalypse, was recorded at the Europa-Sonor studio, rue de la Gaité, with a little help from Roger Roche. The latter, a sound engineer of note, told us a few years ago some far out stories about a recording that is the stuff of legend. Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíou, better known as Vangelis, would have sent for a sex worker in the redlight district just outside the studio with the idea of recording her making love with his personal secretary. He wanted her to appear on the credits of 666, which was strongly opposed by the then president of Vertigo, on which it was released. By contrast, Patrice Quef, who used to be a sound engineer at Studio Miraval, one of the legendary French studios, died last year in obscurity. Other luminaries of that heyday of the French music industry are still living to this day, such as Yves Chamberland, who enjoys a peaceful, though a little too uneventful, if we are to believe him, existence in a DomusVi retirement home in the 13th arrondissement. A few years ago, we paid the legend a visit in his previous retirement home in the 15th arrondissement. The last of the great Mohicans – of geniuses – among those who made major contributions to the art of recording in France, he who created one of the biggest studios in the world where thousands of records, a long run of famous film scores, is still his old grumpy self.

YVES CHAMBERLAND, founder of a grounbreaking French studio is still alive and hitting all the right notes

Manuel Jacquinet: What do you do all day and why do you live here in a retirement home?

Yves Chamberland: I'm bored stiff; there's nothing to do here and the restaurant is expensive. 25-30 euros for a meal (starter, main course, dessert) and it's not even very good. So I go out for groceries; and from time to time, during the holidays, I’m paying a visit to friends or sound engineers, but that was before the virus. Why am I here? Because one day I told myself or I was so convinced that this was the right solution. All my stuff is here now, I left the apartment where I was living. I sold my last car.

Do you remember what led you to create Davout?

I wanted to work at home, in a studio that was my own, and in line with what the clients, the bands asked for. But I don’t remember everything very well, I must tell you. I remember that we had up to four big studios and that the greatest sound engineers came and worked with us. How long are you going to film me with this thing?

(nb: we took notes and filmed with a smartphone).

You worked, before creating Davout, at Europa Sonor and in other studios. And you often went to the United States, at the time, to find the good material, to identify what could make the difference. Where did this passion come from?

I don't remember too well, so much time has passed. So you did a book on studios?

He flipped through the book, looked at the pictures, some of which he paused on, with his mischievous, piercing eye. At the vending machine, he requested a sweet coffee, very sweet, and everything ended in the basement, in a large room of his Parisian lair, far from the Boulevard Davout.

Yves Chamberland: There's never anyone here, and it's big. And I can't play anymore. I was a jazz drummer. I recorded a lot of jazz; I have the tapes of Michel Petrucciani’s concert. I’m going to make a record with them and release it but with all that, I don't have time to take care of it.

Yves Chamberland took off his hat, sat down at the piano and played a few melodies. A video to discover, four years after the Davout Studios closed for good.

Created in 1965 and closed in April 2017, because the Ville de Paris wanted to recover the premises to build a school (which has still not seen the light of day) the Davout Studio was one of the first very large legendary studios in France along with the Château d'Hérouville. Created by Yves Chamberland, musician and sound engineer, soon enough joined by Claude Ermelin, Davout contributed to bringing France among the very great nations in the world of recording. Many film scores were recorded there, but not only: Maxime le Forestier, Prince, The Talking Heads, The Stones came there.

Yves Chamberland then took over the Château d'Hérouville created by Michel Magne. Davout was then taken over by the Putti couple, who made their fortune in girlie magazines, and then Gilbert Castro, another figure of the music industry in France.

Radio France's studios 104, 105 and 106, all located in the Maison de la Radio, are other places where crucial pages of music recording in France were written. All these stories and exclusive testimonies can be found in Manuel Jacquinet's book which was released in November 2020.

Following is a fascinating article, featured in the book, and written by Pierre Lafitan for Guitare Magazine in 1983. Reproduced with the kind authorization of its author.

DAVOUT, AN OLD GROGNARD

There’s no great studio without a great, visionary, sometimes temperamental boss, some would say strong-minded. Reading this fascinating article dating from 1983, one can better understand that Davout, like Ferber or Gang, is not merely a place equipped with a console. Some owners, such as Yves Chamberland, bring vision and conviction to the game. By Pierre Lafitan, Guitare Magazine, 1983.

If you don't go to Davout, Davout will come to you. Yves Chamberland is a fervent practitionner of the motto. Not satisfied with welcoming artists in his home, he goes to meet them, thanks his mobile studio. And not just any artists. In no particular order: Croisille, Salvador, Perret, Cordy, Trénet, Roussos, Mathieu, Simon, Souchon, Ribeiro, Béart, Bécaud, Prucnal; plus the mainstays of classical music and the jazz cats.

Chamberland has no musical preconceptions. Everything that is good and rare is dear to him. His pride: to provide the showbusiness greatest with top-notch tools. Because his is first and foremost a technician. With the proper diplomas (majoring in math, "radio and radar" diploma from the army), he built, as a young man, consoles, microphones, amplifiers, using spare parts found in the American surplus. Later, he built four or five studios, including the first Salle Wagram (in 1958), before teaming up with Jean-Michel Pou-Dubois in 1962 at Europa Sonor. This studio, installed on rue Charcot in a room belonging to a youth club, did not look like much, but provided the amazed geek or enthusiast – brace yourself – with a three-track. The first French three-track. Yves Chamberland reigned over the buttons, visibly happy. Two years later, however, he slammed the door and, in 1965, founded the Davout studio, in a disaffected movie theater on the boulevard of the same name. Davout started with 3 tracks, then quickly increased to 4 tracks, then to 6, 8, 16 (in 1972) and 24 (in 1974). The sound qualities of the Davout studio, which is clear and very spacious (300 square meters), attract the great classical bands and the current stars. As business was thriving, the studio grew. A studio B (much smaller than the A) was created, followed by a studio C (of medium size).

Later, a fourth studio was built for mixing

Men, not only technique, are of paramount importance. From the start, Yves Chamberland had summoned his assistant from Europa Sonor, Claude Ermelin. Today he is the director of Davout, in charge of the planning (Yves Chamberland being the CEO). But Ermelin remains first and foremost a sound engineer. One of the best in the trade, by the way. He is assisted by Roger Roche, Philippe Omnès, Daniel Abraham, and three assistants: Loïc, Fabrice and Jean-Loup.

With its four studios, Davout benefits from a homogeneous complex, one that is very competitive on a technical level. But Yves Chamberland is not one to wallow in self-congratulation. So he is going to renew his equipment. Studio A was equipped last spring with an MCI automatic console. Studios B and C will soon be equipped with a 32-track analog console. Why not consider, while we're at it, a digital one? But no, Chamberland brushes it off. He doesn't seem convinced by digital recording. "Not that I reject technological innovations, quite the contrary. But I consider, and Ermelin agrees with me on this point, that the digital system has not yet completely proven itself. It does not bring radical progress compared to the analog system. I defy anyone to hear the difference between an analog and a digital recording. And with digital recording come many maintenance problems. The machines are very sensitive to weather variations. Not to mention their price, which is absurd and prohibitive. The only way to get digital equipment at the moment is to lease it. That will cost more than 20,000 francs per month. No thanks, I want to sleep at night. Between us, digital is, for the time being, a matter of trade and snobbery. Once the machines have evolved, we shall see.”

If we are not mistakenly understanding his words, digital sound is sanitized, very clean, to be sure, but also lacking breath and soul. And the boss of Davout likes a warm sound, even if it comes from a machine that doesn't look like a million bucks. Proof, the installation of his mobile truck, known as "la poubelle" (the trashcan), with which he makes recordings on stage (Macias, Hervé Villard, Salvador), and sound recordings during TV shootings ("in television, sound is the lame duck"). The "trashcan" is not very sophisticated: an honest console, with small Baxendall correctors, no microphone preamp, but how it performs!

Davout is as proficient when it comes to movies. Because movies and Davout have been going hand in hand for many years. To that end, the studio has a 35 mm 6-track and a 24-track synchronized on the image. The goal: to make a mix either for a potential film music record, or for the cinema, from the multitrack on which we record. [...] "Established" stars, traditional songs, classical music, jazz, live recordings, television, cinema... this already represents a great deal of activity. But Chamberland doesn't want to stop there. He has a PR problem, or so it seems. He doesn't want Davout to be seen as a cushy studio, giving everything in the Mireille Mathieu or Annie Cordy niche. Next step: to attack the young clientele and, in that order, to attract rock bands to his studio A. "Currently, in the United States, rock bands are looking for spacious studios, like ours, with this very "live" acoustic that comes with it. Because space is an asset. I hope that French bands will understand that they have an ideal working tool with Davout A." In any case, the Americans are praising this "Davout A". They recently awarded it a first prize for its exceptional acoustics and performance.

So when will the electric guitars rush to Davout?

The book Secrets et histoires de nos Abbey Road Français can be ordered…

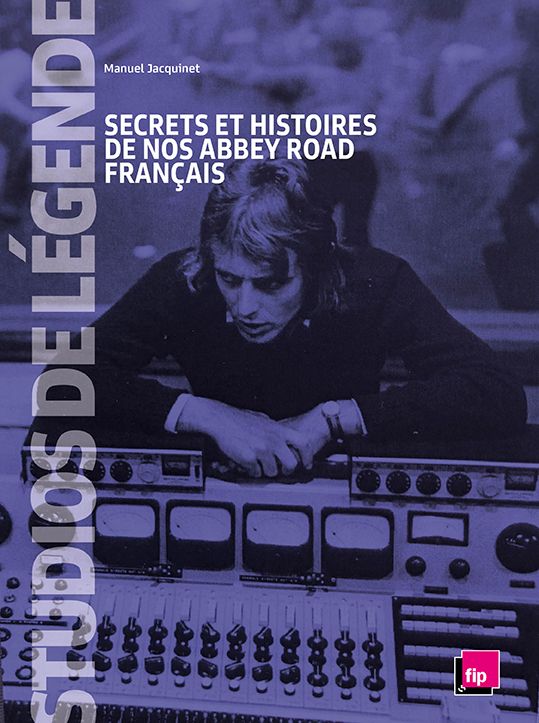

Photo de une : Roger Roche et Vangelis (à l'époque de Aphrodite's Child) au studio de la Gaité - crédit © collection privée