In the Name of Preserves, Chancerelle. Traditional sardines from Douarnenez

In Douarnenez, the fantastic story of a best-selling book devoted to canneries. Sardine canneries.

2020, France. While all the scientists and self-proclaimed experts are discussing Covid on every radio station, a historian from Douarnenez is putting the finishing touches to a detailed, illustrated book devoted to a subject far removed from the standards that make bestsellers successful. The book is devoted to sardines, or rather to canned sardines and one of the major companies in the industry: Chancerelle, the family-owned business that cans the famous blue fish under the Connétable brand. Published by an independent publishing house created specifically for this purpose, the book is almost sold out just a few months after its release, without ever having been sold on Amazon or Fnac.com. One comes away stunned by the book and its long but fascinating read, and even more amused and happy after an interview with the author and publisher. Who are one and the same. Au nom de la conserve Chancerelle (In the Name of Chancerelle Canned Food, which is the title of the book) is nevertheless his first book and his first experience as a publisher.

En-Contact: Alain Le Doaré, who are you?

Alain Le Doaré: I am a Douarnenez native, meaning that I was born in Douarnenez and am the son of a fisherman and a factory worker from Douarnenez. I am a researcher and historian, and my thesis, defended in 1999, was devoted to a fascinating but not very mainstream subject: the birth of priest-sailors, a gradual juxtaposition of missionary models of the Catholic Church in the maritime world in France in the 20th century. It was a work devoted, so to speak, to extraterrestrials: how to share dogma with people who, by definition, are not there, do not have their feet on the ground. From my training as a historian, I have retained a fondness and taste for footnotes and references to sources. Thanks to my family and the place where I was born, I can say that I am immersed in oil. The Penn Sardin, the women who worked in the canning factories, were known as the frying girls. Because of my love of sardines, I am attached to the little things and treasures that need to be distinguished. A tin of sardines has a black or uniform background, but in this one, there are yellow, red and green diamonds. Finally, I live on Nicolas Appert Street, named after the inventor of the canning process.

How did you come up with the idea of writing this book and, above all, becoming a publisher?

Due to my origins, I am concerned and interested in this world, which is close to me and which has provided a livelihood for my family. However, as I write in the epilogue to the book, a researcher must reconcile proximity and distance with their subject of research or narrative. I have been fortunate enough to be involved on several occasions in the history or preservation of photographs or stories relating to the industrial culture of my hometown: Franpac, the first canning factory, was established there, and Chancerelle, which still employs 600 people in a town of 14,000 inhabitants, is the town's largest employer. I have been asked on several occasions to celebrate anniversaries related to the life of the Chancerelle company, which has a rich history, or studies: the one on Franpac, the 160th anniversary of Chancerelle-Connétable, and I was also the curator of an exhibition on ‘the art of fixing the seasons’ at the Douarnenez Museum. I had the good fortune to meet François Chancerelle, born in Brest in 1934, who is one of the 295 great-great-grandchildren of Robert Chancerelle and his wife Jeanne-Rose Giteau, who settled in Douarnenez in the mid-19th century. He methodically preserved texts and photos, which gave me access to an invaluable source of documents. But above all, he always wanted a history of Chancerelle to be written that was neither right-wing nor left-wing, whereas traditionally, in accounts of the working class or factories, it is often left-wing historiography that is favoured. As someone who spends a great deal of time in the archives of bishoprics, which are very rich and therefore real gold mines for a historian, I know how important it is to have access to documents and archives. When I began writing this book in 2018, I visited François Chancerelle, who lives in the Sarthe region, almost every day in September and October 2019. And then I wrote it.

The book is 420 pages long, beautifully illustrated and well researched. You launched the publication without a marketing plan, without a business plan, without even having set up a real publishing house?

Yes, when the text was finished, I launched a small local subscription campaign, which worked well, but I didn't even know how much the book would cost. I managed to raise 8,000 euros. But before that, it had to be laid out. A contact I have at the Bishop's Palace – where, as I said, I often go – advised me to call Stéphane Hervé, whom he knew, and that's how it happened! He is from Carhaix, he is very professional, and we got along well. He chose the printer, Sepec in this case, after working for two months on the book to complete the layout. When all that was done, I had to pay a fairly large sum to start printing, because the printer didn't know me and I think it's quite common with this type of project to ask for payment before production. On 12 May 2020, I received 3.7 tonnes of books on pallets in my garage, 10 of them, I remember; they took up the whole garage! I then took my bike to deliver the first copies to bookshops in Douarnenez and my car to do the same in Quimper. Some journalists who wrote about this book said that Chancerelle had ordered it, but that's not the case at all: they had agreed to buy four copies, but when they got their hands on it, they decided to buy 600 in the end.

The book was published in 2,000 copies, which is already a fairly large print run for a work of this type and was above all an industrial risk?

That's true, but there are only twenty copies left. I now know exactly how much it costs to post, as I send dozens of Colissimo parcels; the PTT charges me £13.50 for each shipment.

So here you are, a publisher, without ever really deciding to become one? And the author of a book that sold well. Is this the beginning of your fortune?

You know, you're the second person to comment on my status as a publisher. A few weeks ago, the manager of my bank, Caisse d'Épargne, called me. The account had just been credited with the cheque for the 600 sales made at Chancerelle, so the amount was unusual compared to what usually comes into my account. But I found myself a publisher just like that, overnight. I don't even have a separate bank account for book sales.

And what about VAT? You do know that you have to declare the VAT you collect, even if it's only a small amount, right?

I know I have to take care of it, but I'm not really interested in all that...

But what interests you then?

Other things, doing things. Years ago, for example, I bought an old industrial building in Douarnenez, which I completely renovated with my own hands and which is now rented out to businesses. What I like is doing things, seeing an idea through to the end. What happens next doesn't interest me much, at least not as much as when I'm writing 10 hours a day. The book, for example, is already almost sold out, and I've already been asked if I'm going to reprint it. But I'd have to withdraw it, find out how many copies there are, and then sell them, that would take time and is much less interesting than creating the book. I recently came across the photo archives of a city photographer, as there were many of them in the 1950s-1970s, you know, those photographers who captured weddings, identities, events in the city or their community. His daughter found them, there are almost 7,000 of them. You can see and sense how, in the 1950s to 1980s, a whole world came to an end, how the paradigm shifted. That will be another book.

What did he think of it?

For his graphic designer, working with Alain le Doaré was also a first. Stéphane Hervé, a graphic designer for 20 years, was the man behind the layout of this shocking book.

‘Everything was very straightforward. The author and I were put in touch through a mutual acquaintance. It took me over three weeks to lay out this incredible story, and I helped him with what I knew best: creating a beautiful book and finding the right printer.’

Find out more

Au Nom de la Conserve Chancerelle was published in May 2020. This superb work of over 460 pages traces the history of the Chancerelle cannery, one of the oldest in France, which is vital to the town of Douarnenez and where millions of sardines have been and continue to be canned since 1866.

The writing of the book began in March 2020, setting aside all the years of work that went into it, and was completed in a month.

Prior to its actual production, the author managed to raise around €8,000 through a local subscription.

Alain le Doaré, publisher.

Customer and employee experience

The Gonidec family cannery, located in Concarneau, is one of the last canneries to offer traditional sardines, caught and canned in accordance with AFNOR standard NF V45-071.

*Au nom de tous les miens (In the Name of All My People) is an autobiographical book, published in 1971 by Robert Laffont and co-written by Martin Gray and Max Gallo. It was a great success and was adapted for the cinema.

Unavailable at Fnac, Amazon or Momox-shop, certain books, records and cassettes are worth seeking out, browsing through and savouring. Meeting their authors and collaborators, often adventurers and free spirits, is a refreshing experience.

Episode 1: Au nom de la conserve, Chancerelle, Alain le Doaré.

Episode 2: Amore Caro, Amore Bello (Bruno Lauzi, Mogol, Lucio Battisti)

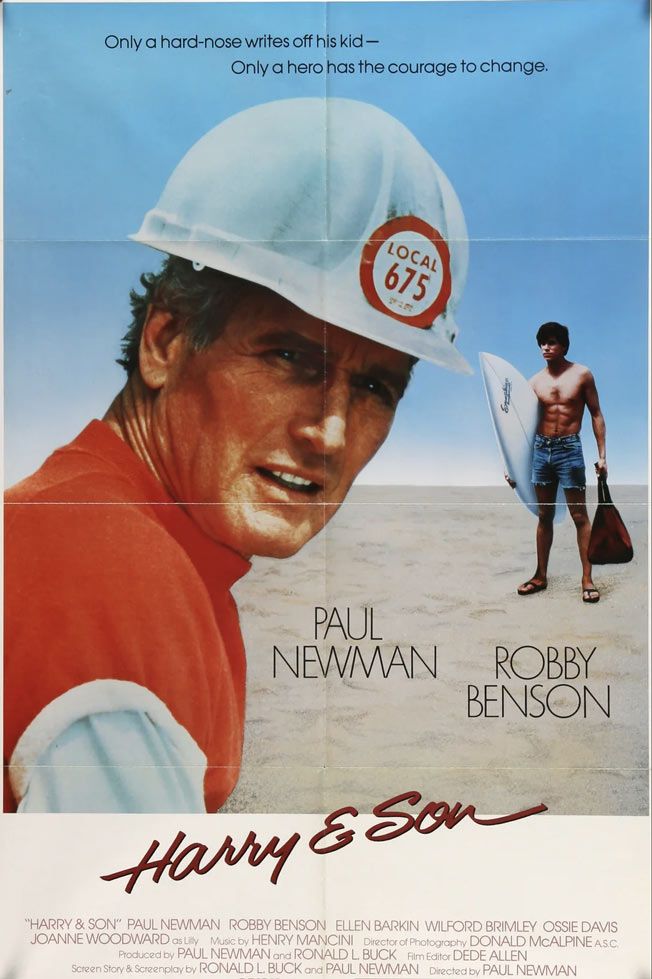

Episode 3: Harry and Son, by Paul Newman (September 2023). Film released in France in 1984 under the title: L'Affrontement.

By Manuel Jacquinet

Read our report on sardines, the foie gras of the sea, here.