Teleperformance was a bit like a cult or McDonald's. Quick promotions without the smell of chips

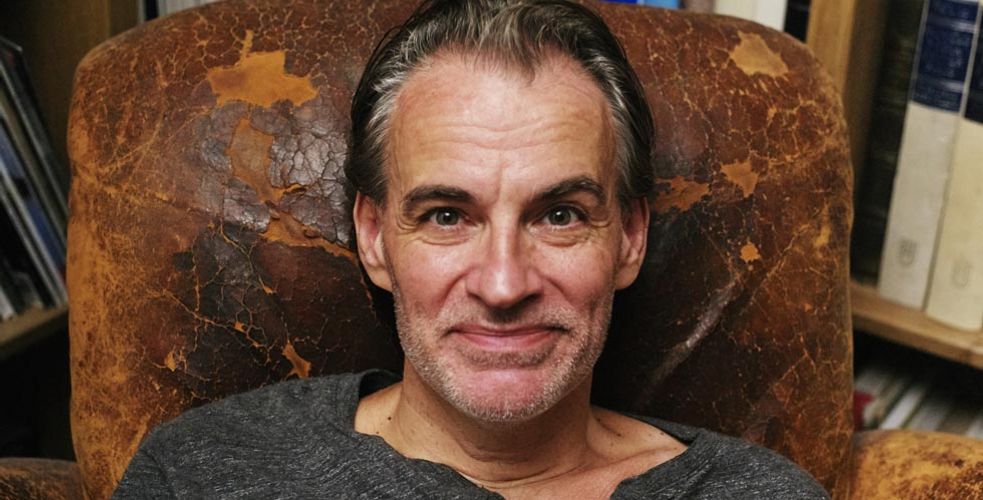

In this second episode of ‘TP's most profitable BU’, Xavier Blanchot, a former Teleperformance technical manager, explains what he believes made the world's number 1 BPO company such a success in the boom years of the Rue Firmin-Gillot era. He now runs the Hôtel La Louisiane, a family business and a legendary hotel.

The 1st major breakdown

My second great memory is the first major breakdown. All of a sudden, when there were forty or fifty of us taking calls, the pie chart - you know, the one that shows the number of calls waiting - started to display: forty, fifty, sixty, two hundred, five hundred, and then I jumped up on the tables and told everyone: you're taking all the calls. Exactly the same scene as in The Wolf of Wall Street (we take everything).

In a single day, we make something like three hundred thousand francs in turnover. I'm jumping from table to table: we're not giving up, I want ninety per cent of calls answered!

My third memory is of having ‘prevented’ Teleperformance, and Patrick Dubreil in particular, from appointing supervisors to the platform who had come from the rue Firmin-Gillot, and of having imposed that one hundred per cent of my disciples all become supervisors first. Most of them are still my friends today, and some have gone on to become directors.

Bertrand Derazey was a TP executive in Tunisia, Philippe Isaac was boss of Belgium, Damien Boissinot was boss of Bordeaux, Bruno-André Giraudon was HR then left for France Télécom with me in another story, Laurent Thomas was a telephony engineer. This whole generation has had an exceptional destiny. For the most part, they were a bunch of graduates with 5 years of higher education who understood that the Internet was going to change the planet and who came to spend six months or a year, a bit like going to McDonald's at one time, before going into management and running a company. We knew we were in the right place technologically. And I got TP to set up a laboratory for research into viruses and telecoms: we dismantled the machines, I turned the set into a geek centre...

Why is it that today, even though you've left the business, this profession and the company still have an image that isn't necessarily very sympathetic, even though it's an extraordinary global success story?

TP has grown first and foremost through its ability to slash prices. It hired young people, including young people from immigrant families. The company has put a lot of faith in these young people, particularly the ‘beurettes’. Teleperformance is a bit like a cult: once you're in, it's hard to get out. I've experienced that in other companies. There's a kind of Stockholm syndrome. In other words, you hate the company but you're attached to it, because we're all suffering together, including the managers.

I think there was a family side to it, but a tough family side. In those situations, real friendships were born, fraternal relationships, a bit like among galley slaves. But there was this capacity for promotion, rapid promotion. If you were good, you could quickly become a supervisor, then RUO, head of an operational unit, and one day you could quickly become head of a subsidiary. Internal promotion was the key, just like at McDonald's, except you don't smell the chips. Here, I've put everything into customer relations.

As in your profession today, which is no longer at all a craft?

The hotel industry has now reached a critical threshold in terms of customer relations, and that's why it's been swamped by Airbnb, which offers experience, friendly relations and a genuine welcome. It has been squeezed out by two multinationals with a host of subsidiaries, Booking and Expedia, with Tripadvisor, Hotels.com, Trivago, Kayak and all the others behind them.

All this is owned by a billionaire called Barry Diller and a bunch of Dutch guys who have gradually taken over and transformed receptionists. Today, receptionists are suburbanites who don't even speak French or English, or speak it badly, and who say: Yes sir, no sir.

They don't know the area because they don't live there and in any case, people have applications to see the restaurants next door which are much more reliable than what their receptionist can tell them.

They no longer know their customers because, in any case, with the laws on sales revenue, Booking can send you a customer at any time. Loyalty no longer exists anyway, because people like to zap. And there's a kind of consumerism: you go and discover the new decor, you go and discover new places, which can be nice, a kind of tourism within tourism in fact. Here, I've completely focused on customer relations: everything is based on the relationship we have with the receptionists, who have been here for a long time, who know the area very well and who love Saint Germain des Prés. We have developed a relationship with artists, writers and academics. That's what La Louisiane is all about.

For the full interview, read issue 134 of En-Contact and part one of this exclusive interview, here.