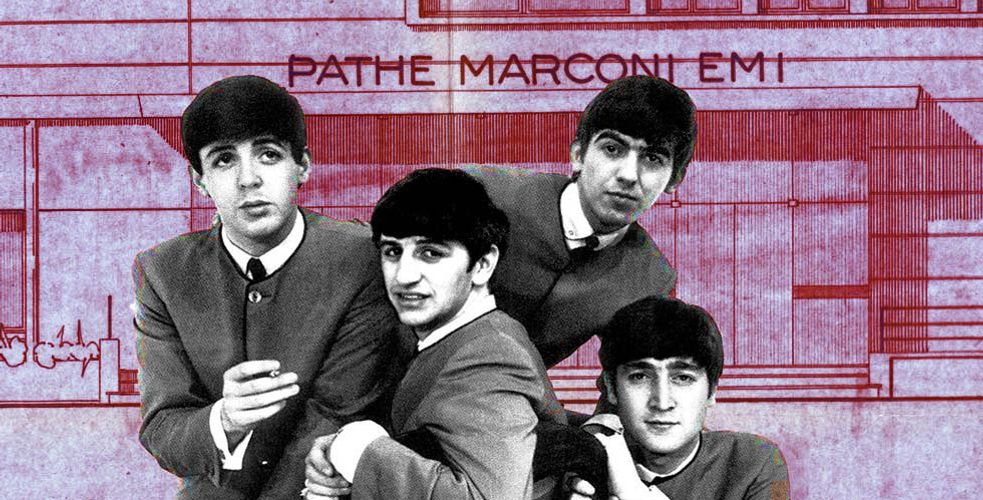

Studio Pathé-Marconi EMI one among the legendary recording studios in France

Five times in a row, the Rolling Stones would come to record here, in Boulogne-Billancourt, in this magnificent studio equipped to the highest standards and where the Beatles, Téléphone, Gérard Manset and all the crème de la crème of French and English rock came. A mini-market has taken the place of this temple of music.

The walls of 62 rue de Sèvres in Boulogne-Billancourt are alive with memories and current events. Past and present mingle together in a strange lament, for those who know how to listen. How many artists have experienced the throes of creation here... That moment that is both delicious and terribly frightening when the red light goes on and you have to ‘go’. Singers, sing. Drummers, beat on. The Pathé-Marconi studio beats like a heart. Night and day. For 25 years. It's on the verge of a heart attack at 45 rpm. No wonder: it's built into a shell. Like a ship. The architects of the 50s didn't lack common sense... They dug to create a structure perfectly protected from outside noise. The result: this studio (one of the oldest in the capital) is one of the best insulated today.

Ground-breaking ceremony in 1958

Those were the (almost mythical) days when singers and musicians recorded two songs in three hours, all at once. Strings and brass (a good forty of them) crowded around the microphones. Producers had an easy signing. Pathé-Marconi was already launching records on the other side of the world, concocted in makeshift studios. A fortune, in fact. Hence the idea of investing in a studio where ‘in-house’ artists would be asked to record, in order to keep costs down. From the outset, the Pathé-Marconi studio stood out for the quality of its equipment. The first Telefunken stereos were installed at 62, rue de Sèvres. Later came the first 4-track 1-inch Telefunken, followed by 8-track 1-inch Telefunken, 16-track Studer and 24-track Studer. René Vanneste, who ran the place from the start and is now retired, has kept a copy of each type of recorder. Excellent for deciphering the tapes that make up the history of showbiz.

In 1959, 62, rue de Sèvres, included three studios, two of which were large, again due to the size of the orchestras in the 1950s. One of these studios has since been closed. Pathé now has a 250-square-metre ‘1’ (with a 50-square-metre booth) and a 100-square-metre ‘2’, which specialises in mixing. The overall design and acoustics are the work of technicians from EMI (Electric Musical Industrie), the parent company.

The studios are currently equipped with Studer 24-track tape recorders. As for the consoles, René Vanneste and his technical team put their trust in Neve. The Neecam automatic remixing system is the next step in the computerisation process. A must! As far as special effects are concerned, the Pathé studio is perfectly placed: a natural chamber, an AKG BX20, an EMT 140 and two digital EMT 440. One original feature: all the period microphones (U 47, M 49, etc.) have been kept here. Some bands, like the Rolling Stones, are very fond of old tube mics. If they come here, it's largely because of the microphones.

Another of Pathé's strengths: engraving. For several months now, the rue de Sèvres studio has been equipped with ‘direct copper engraving’. The ‘mother’ is engraved directly, eliminating the intermediate operation of engraving the acetate lacquer. This new engraving system, which makes it possible to go directly from the strip to the master, is called ‘DMM’. Advantages: better quality and time savings (four operations eliminated). You might think that the Pathé-Marconi studio (sponsored by the record company of the same name) didn't care about publicity. But no: Pathé is also positioning itself as a service provider and is accepting more and more external clients (around 35%, compared with 25% ten years ago). To attract and retain these customers, we need to constantly improve our facilities.

Studio pro

The ‘2’ booth (Yves Duteil's favourite studio) has just been acoustically redesigned and enlarged. (New surface area: 35 square metres.) available to Pathé artists (Gilbert Bécaud, Franck Pourcel, Jacques Higelin, Richard Dewitte, Karim Kacel, etc.) and others: an available and motivated team, led by Bernard Ray, previously assistant to René Vanneste. Claude Wagner, Roger Ducourtieux, Daniel Michel, Pierre Saint (sound engineers), Bernard Camus, Bernard Rey, Claude Pothet (maintenance and technical service), Jean-Claude Pellé, Louis Baroux (engravers), Guy Peter (master-duplication), Roland Faure (copying work and restoration of old documents), Driss Joual (stage management), Aline Bounon (secretariat). In addition to its facilities in Boulogne, Pathé-Marconi has a studio in a room at the Salle Wagram, equipped with an EMI-Neve 32 x 24 console and a Sony 2-track digital recorder. Pathé is also into classical music.

Source : Guitare et Clavier, Pierre Lafitan, 1986

The creative spirit of the Pathé studios

When Pathé inaugurated its Boulogne studio in 1960, the event was such that the Minister of Culture came to attend the official ceremony. While the British and Americans had already built buildings designed by architects and acousticians for recording purposes, no equivalent yet existed in France. The first real studio had just been built!

Did you know that, just after the Second World War, people were still content to listen to 3 minutes of music per side on 78 rpm records? Fortunately, from the early 50s onwards, the LP revolutionised technology. Its sound quality proved excellent, and we could now listen to up to 30 minutes of music on each side. A revolution!

It was at this time that Pathé, a company founded in 1890, moved from its hangar on rue Pelouze to rue Jenner, in Jean-Pierre Melville's former film studios. ‘We were moving up a gear. About fifteen people worked there, and we sometimes bumped into actors like Alain Delon, Mireille Darc and Brigitte Bardot,’ recalls sound engineer Alain Butet. The studio was equipped with natural echo chambers in the basement, while the auditorium had a country atmosphere to say the least... The acoustic treatment had in fact been devised... by stacking bales of straw! Claude Wagner, who started out as Alain Butet's assistant before becoming sound engineer at the Boulogne studio, remembers those days: ‘The assistants wore white coats and I was one of the first to refuse to wear the technician's uniform that was being imposed in the house!

Pathé brought together the La Voix de son Maître, Columbia, Ducretet-Thomson and Odéon brands, and records were burnt and pressed at the Chatou plant. Pathé also manufactured audiovisual equipment such as electrophones and televisions.

‘Entering Pathé was like taking holy orders’.

In 1960, Pathé moved from Melville to Boulogne. It was the first time in France that architects and acousticians had designed a building entirely dedicated to recording. The new complex had four studios, six natural echo chambers and employed up to six sound engineers, six assistants, a maintenance team and a director... At the time, the studio was seen as a creative tool with no performance imperative! ‘I spent hundreds of hours on many recordings that were never marketed,’ says Claude Wagner. When the cost of the studio became an issue, it was initially decided to close one of the cabins, before completely demolishing the building in 1991. At Boulogne, I was lucky enough to record Gloria Lasso, Luis Mariano, Bourvil and Franck Pourcel,’ says Alain Butet. We knew our schedule a year in advance, depending on the album releases announced by Pathé. Among the anecdotes recounted by Alain Butet, one is particularly revealing of the in-house climate. You entered Pathé as you would an order, so it was not tolerated for employees to go and see how recordings were done elsewhere,’ Alain Butet explains. Yet I took the initiative of visiting the English studios at Abbey Road, where I discovered that they were using Neve 24-channel consoles and 8-track recorders, whereas we only had 4-track recorders...’. The head office in London regarded the Boulogne studio as a branch; it was the poor relation, taking over equipment that the English studios no longer wanted or buying second-hand from other French studios. In London, I also had the privilege of observing the Beatles recording,’ continues Alain Butet. But on my return, I was told that I was no longer working at the studio, having broken the sacred rule of not going elsewhere. Fortunately, the support of my colleagues and musicians enabled me to regain my position.

Nervous breakdown for Chats sauvages...

The Beatles, on the other hand, came to the Boulogne studios once. It was in January 1964. The group was in Paris to perform at the Olympia and the German subsidiary Odeon of the EMI group wanted German versions of certain hits. ‘When their producer George Martin turned up at the studio, the Beatles weren't there,’ recounts Mark Lewisohn in his book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions (Hamlyn-E.M.I.). He waited over an hour before calling the four musicians at the George V Hotel. ‘They're asleep and don't want to go to the studio,’ he was told. Furious, George Martin jumped into a taxi to fetch them. ‘Surprised over a cup of tea, they stared at me in bewilderment, before disappearing like pupils running away from the arrival of the teacher! recalls the producer. I shouted and a few minutes later we were on our way to the studio...’

‘We used to wait for them with wigs imitating their long hair’, recalls Claude Wagner, who continues: ‘The arrival of rock & pop groups changed our status. We became another member of the group, chosen by the musicians. We were given a lot of freedom to come up with new sounds and experiment with every conceivable sound. The musicians were often very young and not always up to speed with their instruments... It is said that the soundman Jean-Paul Guiter, a jazz specialist who also worked with Dick Rivers and his Chats sauvages, used to have veritable fits of nerves when he had to edit a guitar solo from dozens of takes... ‘Problems also arose with the recordings of the musicians. Problems also arose with French groups who asked us to create a particular sound inspired by Anglo-Saxon models,’ recalls Claude Wagner. When the drummer of one of these small groups asked me why he didn't sound like Billy Cobham using the same drums, I replied: ‘You know, I've got the same bike as Eddy Merckx but I've never won the Tour de France.

Pathé, so close to Abbey Road

Founded around 1890 by the Pathé brothers, in less than 20 years the company had become one of the largest film production and equipment companies in the world. At the same time, it was also a major producer of phonographic records. In the 1930s, this record production was absorbed by the English group E.M.I., best known for its London studio at Abbey Road.

Source: All accounts in this article are taken from Soundcheck, special edition, 1991, reproduced in ‘Studios de Légende, secrets de nos Abbey Road français’.

Studios de Légende, secrets et histoires de nos Abbey Road français

Beautiful book with exclusive photographs. 352 pages. Weight: 1.3kg!

Published by Malpaso-Radio Caroline Média.

45 euros.