A good location is expensive

Rent for hot-dog stand locations up to $250,000 in the most frequented parks in NYC (New York City).

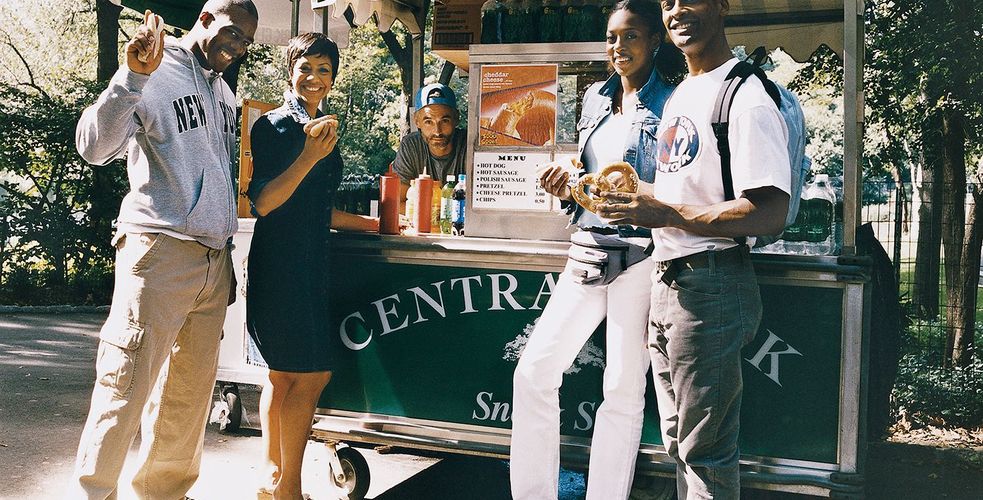

The acquisition of customers is expensive and can even reach extravagant amounts. Being in the right place – in the physical world like in the digital world- represents a real risky investment because nothing is ever guaranteed for a long time. New York gives a triple illustration of the principles and rules that define the idea that loyalty is key. Last but not least, data analysis is at the heart of profitability.

Call it the half-million-dollar hot dog cart. Mohammad Mastafa of Astoria, Queens, has to sell almost that much in drinks and snacks each year to break even on the pushcart he owns at Fifth Avenue and East 62nd Street right next to the Central Park Zoo. He pays $289,500 a year to the city’s parks department for the right to operate his cart there.

It may seem like an exorbitant amount of money, but it isn’t shocking to many of the other food vendors – like Mr. Mastafa – who compete to operate pushcarts in New York City parks.

The zoo entrance is one of 150 spots in and around the city’s parks and fetched the highest price at auction, but the operators of four other carts in and around Central Park also pay the city more than $200,000 a year each. In fact, the 20 highest license fees, each exceeding $100,000, are all for carts in Central Park.

“It’s a lot of peanuts, it’s a lot of hot dogs”, said Elizabeth W. Smith, marketing assistant for the Commissioner of Municipal Parks.

It is certainly a lot of people in search of food. While vendors are very reluctant to divulge any information on their business, most vendors presumably turn a profit or the sites would not fetch such high prices at auction.

The annual fee some vendors offer to pay the city has doubled or even tripled in the past 10 years.

A decade ago, the fee paid for the pushcart at the Central Park Zoo entrance was $120,000, less than half what Mr. Mastafa paid recently. The next most expensive cart is on the West Drive at West 67th Street near Tavern on the Green, where the fee is $266,850.

For many other parks, especially those in parks outside Manhattan, the fees are much lower — $14,000 in Astoria Park in Queens, $3,200 in Maria Hernandez Park in Brooklyn and $1,100 in Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx. The lowest fee – $700 – is paid by the owner of a cart near the football fields in Inwood Hill Park in Upper Manhattan.

Elizendo Vaquero, 50, of the Bronx, has been selling there to football players on Sundays since 1989 (since 1997 with permission).

“Everybody knows us here”, he said. “This is like family.”

He said he bids a little higher every time he has to renew the lease, but still earns $3,000 to $5,000 a year from his cart. “I don’t want to lose this place”, he said. “We have to pay the employee, the permit, everything. But at least we’re happy. We see everyone.”

The Parks Department’s concession stands are put out for bid every five years and produce more than $4.5 million annually for the city’s administration fund.

The vendors who work at these stands aren’t usually the owners. Ripan Alam, 31, typically works for Mr. Mastafa from 8:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. in the summer and says he takes in about $750 weekly, although the revenue produced by sales from the cart fluctuates wildly. “When it’s raining, sometimes empty, nothing, zero,”, Mr. Alam said the other day. “Often it’s empty. Monday and Tuesday, nothing.”

Pushcart operators also complain of growing competition from disabled veterans who work from locations outside the park on the perimeters, and who can charge less because their license fee to the city is significantly less due to a 19th-century law.

According to some of the vendors, sometimes other people own the carts and pay veterans to work them. That indirect relationship is a problem that parks department officials acknowledge, but say they are largely helpless as the police have much more power, especially since the city is appealing court rulings that would expand the veterans’ rights to sell. (Food carts outside the parks have a separate licensing plan ran by the city’s health department.)

Mr. Mastafa – like the other operators interviewed – refused to report his pushcart revenue. In the industry this mistrust is due to the fear of competition in bidding when their licenses expire, tax confidentiality and their relqtionship with their wholesalers.

Alex Rad, one of his suppliers, explained that the economics of the pushcarts are more complex than you might think. During Hurricane Sandy last year the parks were shut and, since the Boston Marathon bombing, vendors are sometimes chased out from large public gatherings by the police. “Some locations are losing money,” Mr. Rad said.

Mr. Rad has a partnership with New York Picnic Company to supply many of the Central Park concession stands. He says the stands all have secondary costs, such as paying $20 or so for each delivery of ice several times a day and the transportation of their carts from garages or warehouses. He estimates that if he wants to cover his expenses, Mr. Mastafa’s concession stand at the zoo needs to generate more than $425,000 a year.

“We’re dying”, said Ranjit Dev, whose company owns several desirable sites around Central Park. “How can I pay $180,000 if I can’t sell? How am I going to pay the rent?” Construction sites near the Metropolitan Museum of Art has helped reduce sales in what was once a prime location.

New York is a city of superlatives, so the 40 million or so visitors to Central Park a year obviously buy a lot of bottled water, ice cream and other refreshments. Maximum prices for snacks and drinks are set by the Parks Department.

Seubankar Ray, who works at a stand at Central Park West and West 72nd Street, said bottled water is his best-selling item, although sometimes even New Yorkers flinch at the price. “They say, ‘That’s $3? Oh, my God! I’m not a tourist.’”

In July, even at that price (the maximum for a 750ml bottle), he sold 15 cases a day. On a regular day he sells up to 200 hot dogs a day at $2 each. He said the stands take ranges from thousands of dollars a day on a warm summer weekend to $200 in the winter, when he sells mostly hot dogs and peanuts.

Another pushcart operator, Mr. Amin, who agreed to be identified using only his last name, said the cart he operates at West 67th Street and the West Drive can make as little as $50 a day in the winter, but $2,500 on a Saturday in Summer.

At his cart, but not exclusive to it, sweaty runners finishing their laps ordered ice cold Gatorades according to their colour — yellow and orange were the most popular — but water still appeared to be the top seller at certain locations.

“What we sell mostly is water”, Mr. Alam said. “Children love the snow cone. The over 60s group like the Toasted Almond. Most locals like the hot dogs. Italians think that sausages are like this big” — he spreads his hands about a foot apart — “so they say, ‘Can I have one?’ And when they see the actual size of it they don’t want it anymore!”.

Source : New York Times

To order the book, click here.

Read more from Business is business, here.